Author: Nikki Henderson

Moulding, lamination, composite sandwich construction, resin-to-glass ratios; these are still words that can send me into fight or flight mode. As I walk into boatyards, particularly if I’m having a less-self-confident day, there can be an overwhelming urge to walk slowly in reverse back out the door.

My shoulders hunch. I stand awkwardly shifting weight from one foot to the other. I uncross and cross my arms, alternating between hiding my hands in pockets or elbows, or putting them on my hips. I often find myself staring intently at the boat builder, willing them to look at me on equal terms to my colleague as they talk the technical jargon. I have to fight the mostly unfounded rhetoric in my head that is I don’t belong.

Know what I mean?

Explaining to a friend the other day, I used the synergy between a boat yard and a car garage. I recalled a story from back when I was 17. My Nissan Micra was due its MOT (annual vehicle check). Pushing open the greasy door I walked into the reception of my local garage wearing my pink jeans, painted fingernails, and the stubborn remains of pubescent acne on my chin.

Standing at the high counter and not quite knowing exactly how one should ask this, I said in an unusually quiet voice “Hi. Do you do MOTs for Nissan Micras?” “Yep.” The mechanic replied, looking back down at his magazine and flicking the page whilst he said it. “Bring her in tomorrow. £46 as long as we don’t find anything wrong.” I smiled sweetly, said “thank you very much”. My heart was racing. I felt thankful not to have been asked further questions which would have proved how little I knew.

Once in the car I remembered my father saying an MOT generally costs between £30 and £35. However, despite my usually distinctive confrontational and confident nature for a 17-year-old, I brushed it off and assumed the price must have changed. I’m not sure whether it was my ignorance in an unknown environment, or the tone of the interaction, or the lack of people who looked like me – but something in that reception made me extremely hesitant to return.

Once home, I told my father about the increase in price. Later that afternoon, he called the garage and spoke to the same man, without revealing details of his daughters’ visit that morning. Within five minutes, my car was booked in for its MOT for the price Dad was quoted: £35.

High counters in garages – just like boat yards, or engineering departments, or PCs running complex modelling software, or formal office suites – can often feel like impenetrable barriers. This is particularly marked when you don’t match with the person or people on the other side of the boundary. If you look different, or wear different clothes, or are a different age, sex, race – it can feel like you don’t belong. I learned when I was 17, that this can have more serious consequences than just feeling uncomfortable. It’s easy and arguably justifiable to fear being ripped off, or forced to make an uninformed decision, or cast aside for a better fit.

This is why, when I first visited Outremer HQ, I was very surprised to hear that first on the agenda of the day was a tour of the shipyard. As we walked to the yard, I was further taken aback to hear that every prospective Outremer owner gets a full yard tour. Matthieu explained that he gives most of them. Nicknamed “the Outremer Bible” by his colleagues, highlighting their admiration for his vast knowledge of the Outremer family past – present and future – it’s an understandable job for Matthieu to oversee.

Since my first experience I have enjoyed two more-yard tours. Most recently I toured with Benjamin, Matthieu’s deputy, who isn’t far behind him in not just Outremer history, but also passion for what he sells. In December, he was excited to show me “his cabin” on a new 55’ that was being built. Having formed a friendship with the new owners, Benji is planning to use his annual leave to take up their invitation to join them on their first Atlantic Crossing. I was surprised. I don’t often hear of a salesperson who is prepared to set sail to a point 1500 nautical miles from land on their product. And with their customers. It felt like a rock-solid sign of Ben’s faith in the boat’s safety and seaworthiness, and the relationship Outremer builds with their owners.

To date, these make up the only yard tours I have ever had. As a young ‘nipper’ in the sailing industry, my experience in boatyards has always been ‘learn on the job’, so I never had a chance to ask too many questions (or perhaps that was my ego stopping me…).

I have written this blog to share my experience. I’m aiming to break down boatbuilding and the language surrounding it. If I can demystify the ‘dark art’ of boat building and prove that it isn’t only suited to the crustiest old sea dogs with a parrot on their shoulder, then I feel that’s a step in the right direction. In time, I hope to see more diversity within yards, and the sailing industry, and I think one of the most important steps is to make it feel approachable and inclusive. Enjoy. And please do not make the same mistake as me, and ask as many questions as you like!

1/ History

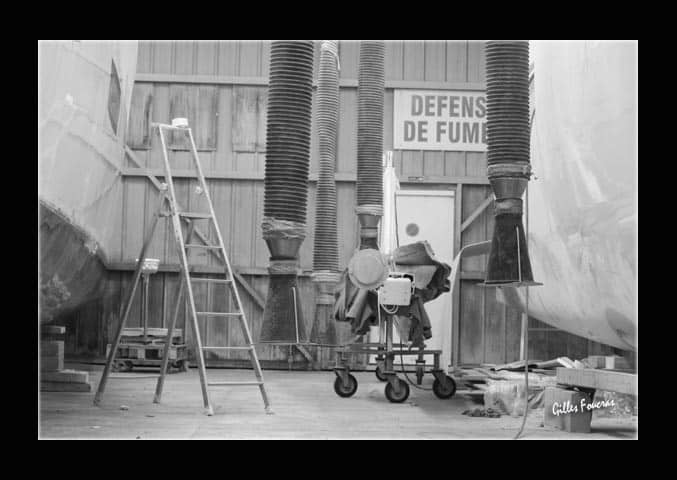

Thirty seconds from the office and we stood in front of an old factory. Just steps away from the glass doors of Outremer’s HQ was the original warehouse where the first ever hull was built back in 1984. Above the door was the faded word ‘Outremer’. The sign now, like the company, is 36 years old. La Grande Motte’s scorching summers and wet winters have left it only just legible. Once we entered the warehouse, the floor surface was noticeably uneven. On closer inspection, the bumps under foot were layers upon layers of resin: the by-product of decades of glasswork in an old factory without modern temperature management systems.

The juxtaposition of old and new is very quaint. Outremer’s deep-rooted heritage provides a trustworthy and comforting foundation to their product. Like an old recipe of your grandmother’s, their boats feel predictable, reliable, safe. This softens the harsh white of the hulls. It adds a deeper story to their professionalism and sincerity. It allows them to commit to more contemporary designs and construction without seeming reckless or risky. Their boats are modern machines. But the 20+ knots of boat speed and precision engineering doesn’t feel superficial. It feels like it has been born from commitment, years of experience and hard-earned stripes.

2/ Moulding

The first stop of our yard tour was ‘moulding’. I was struck by how dense and massive the moulds were. The boats are so light and hollow they barely touch the water’s surface when they are first launched. The moulds were a dramatic contrast. This is where most of the money goes, according to Benji. They are extremely expensive, and they last for a maximum of 10 hulls before their imperfections require them to be replaced. With each replacement comes an opportunity to tweak the design. For example, a gas locker hatch door was recently moved with the mould replacement. Just a few mm across allowed it to now be opened fully without removing the wheel.

Even such minor inconvenience for owners like this is listened to and improved at the first opportunity.

Onto the mould, I was then shown how the hull was built – layer by layer. First the mould is waxed to stop anything sticking. Then the gel coat is sprayed on. For anyone who doesn’t speak the jargon: imagine white nail polish. Then one very thin layer of fibreglass is hand laminated onto the gel coat with resin. The whole glass and resin thing is easiest understood as papier-mache; the resin is the flour and water glue (heavy), and the glass is the tissue paper (not heavy). Memories of my adolescent piggy bank built around a balloon come flooding back to me.

As layers of glass are then added, so are very dense foam panels in the middle (‘foam-core’) to reduce the weight. In places that need extra strength, such as the self-tacking jib traveller location, the foam is replaced with aluminium. Interestingly, a strip about 2 feet wide runs down the underside of each hull and is pure fibreglass, for extreme stiffness and strength in case of impact. The density difference is astounding. As I picked up two pieces of identical looking glass, the foam core was light enough to throw across the room, whereas the pure glass needed two hands to lift it.

Finally, the hulls are vacuum bagged. The meaning of this is literal: plastic sheet, tape and suck air out. Then resin is pumped in through tubes, and excess is sucked out. This technique is all about ensuring optimum strength to weight ratio. If you take yourself back to the piggy bank, ideally you want enough glue to ensure it all sticks but not so much there are drips and over thick areas in the wrong places making it less than round. Before they used vacuum bagging, they painted the resin by hand, and identical hulls varied by as much as 0.5 tonnes.

As I said before, despite my ‘professional sailor’ status, I learned loads in this first part, having only really laid fiberglass with a paint brush in what now feels like an embarrassingly similar technique to that of my adolescent papier-mache models.

This is the kind of inclusive behaviour that changes the world in small steps. Diving straight into the tech stuff and not the cushions immediately put me at ease that I would be treated as an equal, interested, keen customer. It felt a million miles away from how I felt in that garage 10 years ago.

3/ Assembly

The boats are built in four parts: Port side hull, starboard side hull, bridge and inside two hulls (H shape), and then the top (deck). ‘Assembly’ means they glue all the parts into one. The joints are laminated from both the inside and outside. By laminating I mean more fibreglass work, this time overlapping the joints like a bandaid.

Once the side hulls and bridge are assembled, then the bulkheads are added in. They are made of the strong stuff: carbon epoxy or a similar fibreglass foam sandwich as the hull. The secondary bulkheads are made mostly from a sandwich foam core, whereas the dividers in the hulls that make up mainly the bilges and bed or cupboard frames are made from plywood. Also, at this stage the mast section is reinforced. Unlike a monohull whose mast is stepped to the keel, here it is essentially bolted down (stepped) to a mini tree-trunk. Not kidding; it’s 4 large pieces of wood that make up a 0.5mx0.5m square. Then all these bulkheads are laminated to the hull in the same fashion as the hulls themselves.

4/ Installation, Deck Closure and Interior Finish

Once the hulls are assembled, the plumbing, electrics and other systems are put in. The furniture also goes in around this. It comes ready made from a carpentry factory offsite that is owned by Grand Large Yachting. It’s a very similar experience to buying a kitchen. Outremer has their standard design, but you can change the colour, or quality of the finish to your budget and taste. Everything arrives a little bigger than it should be and they cut it down to ensure it fits perfectly.

Installation is where laminating turns to sealing. No more papier-mache; the interior furniture is sealed in with Sikaflex. Sikaflex is very similar to the sealant you use to seal around your bathtub or shower. It is used because it has some movement tolerance which prevents cracking. Together with the extremely stiff hull (due to all the lamination), the result is an incredibly quiet stiff boat whose cupboard doors still open and close after 10000 miles of slamming across oceans.

This third warehouse was a hive of activity. Workers were everywhere: under boats, on decks, on the roofs, on scaffolding on the sides. The teams were all friendly and clearly used to welcoming guests. The industry tends to accrue global teams due to sailing’s transient characteristic. Whilst there that day I met a Californian painter with dual nationality, a Kiwi electrician, and of course plenty of local craftspeople. The teams tend to hire younger workers and train them on the job, so there is a certain mentor/mentee feel about the place. The long-standing nature in the company seems to run through the staff. Not only Matthieu has been there for decades; one of the yard boat builders just left after over 30 years working for the company.

5/ The finale

A boat is not just her dimensions, or her specifications, nor simply a collection of materials, fittings and fixtures. A boat is also a personality. She is a story; an outcome of years of time, love and dedication. A boat is all of those things and then she becomes more, as she matures, fades, and colours with the miles she sails and the owners she belongs to.

Therefore, it is understandable that the final stages of splashing and commission are emotional for everyone, and not just the owners who have invested close to 1 million euros at a minimum. The boat is a symbol of what Outremer hopes to represent: honest and human values, bespoke design, durability, family exploration, safety, beauty, performance. Everyone gathers to watch as she is driven out on the back of a lorry and exposed to the beating French sun for the first time. She is then craned up in slings and pulled over the dock’s edge. Ropes on her four corners, she is stabilized by hand against the gentle afternoon sea breeze.

One morning in December 2020, I had the privilege of sharing the launch day of a new 51 with her two owners. As they watched their new boat hovering above them their hands grasped together tightly, their knuckles whitened, and their breath shortened. I could sense their anticipation and nervous excitement. The gateway to their dream life was being lifted high into the air. As the boat splashed down – and floated – their sigh of relief was audible, as was a cheer from the rest of the team. The pride for their work was clear: another new personality gracefully accepted by Mother Nature.